Caveat Emptor

This past week we’ve witnessed a story of drama and tumult in the stock market; of great successes and stinging losses; of individual investors taking on the institutions. And subsequently, of cries of elitism and unfairness. All stemming from everyday investors, connected via a social media community, wildly buying shares in an unprofitable stock, GameStop.

While there are numerous storylines in this saga, I will focus primarily on one: the calls of unequal, undemocratic, treatment of individual investors relative to hedge funds. The discussion – furor – is born of a belief that this is class discrimination institutionalized by our financial system. What we’re actually witnessing is something considerably more complex.

Despite the clarity and simplicity to which we as financial advisers distill sound investment principles, the equity markets are fundamentally confoundingly complex. On the surface it remains true that good investing can be as straightforward a notion as buying a broad array of stocks and bonds through low-cost funds, and holding them for long periods of time. The reality is that underneath that idea exists a vast and dizzyingly complex array of market infrastructure, and tools with which to navigate it. Those who venture beyond their understanding of the variables and the risks which underly them expose themselves to the potential for great pain. Others who do not understand how these plans went awry stand to fan flames where there is little or no fire.

Our careers as CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ professionals, beginning as individual investors spanning a combined 70 years, have come full circle, from the wide-eyed enthusiasm and simplicity of beginners to the more sober contemplation of the vast power and complexity of the financial markets. Along the way, from passing exams to be stockbrokers to the CFP® exam to starting our own Registered Investment Advisory firm to absorbing the wisdom gleaned from professionals in various roles in the financial marketplace, we have had numerous occasions to pause and ponder the many ways we and other investors could get hurt by forces we might scarcely comprehend or foresee. The result is a certain humility; a discipline to focus on the tools to help our clients accomplish their goals; a recognition that not all that is more complex is “better;” a condensation of thinking back to the clear, the efficient, the balanced. Above all, our experience has taught us a healthy respect for the marketplace.

If only a greater number of investors saw things this way. Think of baseball. It is quite simple on a fundamental level: “see ball, hit ball.” Yet Hall of Fame manager Tony LaRussa once said of the game: “There’s a lot of stuff goes on.” In his book Men At Work describing the rich nuances of the sport, George Will chronicles the remarkable complexity in motion throughout the game, much of it completely oblivious to the casual fan. Capital market are not dissimilar.

We have often described investing as akin to swimming in the ocean. Between growing up on the coasts, Peggy being a veteran of the US Navy, and me being a former ocean lifeguard, we have developed a considerable respect for the dangers which the ocean presents, in addition to its many adventures and pleasures. In the capital markets, we realize that we’re swimming in an ocean so deep, potent, and unpredictable as to foster a considerable respect for its grandeur and its ability to do us harm. Eventually, we begin to see deeper, possibly even making out some outlines of what might be the ocean floor – the outer, defining reaches of the landscape – which may or may not actually represent our comprehension of the scope of our environment.

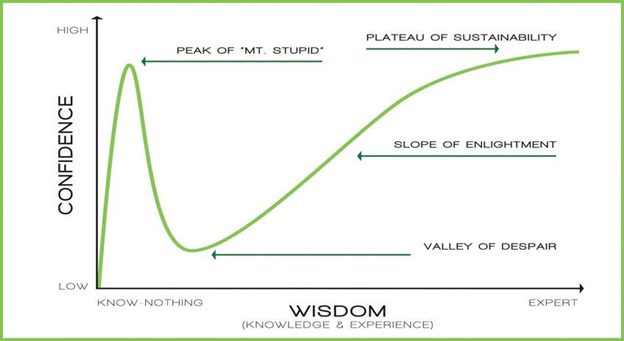

Unfortunately, before we benefit from this perspective and this respectfulness, we overflow with ill-placed confidence. Enter the Dunning–Kruger effect. Below is an illustration of its principle:

The voices we hear loudest this week are coming from the left side of this graph, including, sadly, from some lawmakers in Congress. Would they decry certain brokerage firms’ one-day restrictions on buying additional shares of a select few companies if they understood that certain capital requirements – cash deposits on hand – are required of these firms to ensure that they can actually complete trade orders they receive? When the trading ledger of an individual brokerage firm becomes so unbalanced between outstanding buy and sell orders of a particular stock, the clearing firm which settles the trades is entirely prudent to raise the reserve deposit requirement of Robinhood, in this case. That’s not slighting the small trader. That’s business risk management. Investors, meanwhile, were always free to buy additional shares of these few restricted stocks through any other brokerage firm. And never did any brokerage firm prevent any shareholder from selling shares of any of their positions. That would have been alarming. It never happened.

Have there been improprieties orchestrated in this market drama? That’s possible; yes. But to understand equity markets is to recognize that smooth and orderly execution of trades depends on elements and systems that have evolved to facilitate a robust and timely matching of buyers and sellers. This market infrastructure includes short selling, large firms of “market makers,” and financial requirements of brokerage firms, to name just a few. This is not unethical. For every buyer or seller, there is a ready taker with the opposite opinion for the prospects of that stock. We know a financial professional who once told me that trading options equates to “guaranteed income.” Wow. Such arrogance fails to recognize that successful investing is not a game.

Robinhood and other online brokerage platforms have indeed democratized trading, as they proclaim. By reducing trading costs to zero, allowing fractional share purchases, and displaying confetti on the screen when a trade is made, they have attracted a new cohort of investor. Significantly, not only are these new investors commonly inexperienced, but many also turned to individual stock trading to replace the absence of sports betting in the early months of the pandemic. Social media platforms have acted as an accelerant to their fervor. Robinhood offers a platform where stock trading includes a thrill. (Who doesn’t like a thrill?) They promote margin trading (where brokerage firms do make money) and other tools ill-suited to those who do not comprehend their inherent risks. What Robinhood, in particular, has provided is the freedom and the means for these inexperienced investors to shoot themselves in the foot, potentially doing material damage to their financial futures.

Investing is not an adventure. It is a demeanor; a mindset. It is a patient discipline; a long-range process. May we all respectfully treat it as such.